Short-lived climate pollutants (SLCPs) are potent climate forcers with atmospheric lifetimes significantly shorter than carbon dioxide, ranging from days (e.g., black carbon) to a few decades (e.g., methane). Despite their transient presence, SLCPs have high global warming potentials and contribute substantially to near-term climate warming. Black carbon and methane directly impact communities by intensifying air pollution and climate extremes, undermining livelihoods and increasing economic losses, particularly in low-income and climate-vulnerable regions. Black carbon and tropospheric ozone contributes significantly to premature deaths and respiratory illnesses in India, with air pollution being a leading risk factor for public health, especially among children and the elderly. 10% of the total disease burden in 2016 was caused by air pollution levels. Methane and ground level ozone reduce crop yields of staples like wheat and rice by damaging plant tissues, posing a direct threat to food security and farmer incomes, which is significant in India's extensive agrarian landscape.

What are SLCPs?

Short-Lived Climate Pollutants, are non-CO₂ atmospheric agents with high radiative forcing and relatively short atmospheric lifetimes. They include methane (a potent greenhouse gas), black carbon(a light-absorbing aerosol), tropospheric ozone, and hydrofluorocarbons, all of which influence climate and air quality. Due to their short persistence, targeting SLCPs enables rapid climate mitigation and co-benefits for human and ecosystem health.

SLCPs FOOTPRINT ?

Short-lived climate pollutants— black carbon, methane, tropospheric ozone, and hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) —are the most significant contributors to anthropogenic global warming after carbon dioxide, responsible for up to 45% of current global warming . Without action to reduce their emissions, they could contribute to as much as half of human-induced warming in the coming decades.

Methane

(CH4)

- GWP: GWP 20 years: 81.2 | GWP 100 years: 27.9

- Atmospheric Life Span: Around 12 years

- Top Emitters: Agriculture, Fossil Fuels and Waste

Black Carbon

(BC)

- GWP: GWP 20 years: 1500 | GWP 100 years: 460

- Atmospheric Life Span: 4–12 days

- Top Emitters: Burning of fossil fuels, wood, and other biomass fuels, as well as waste

Tropospheric Ozone

(O3)

- GWP: GWP 20 years: 918-1022

- Atmospheric Life Span: 1 to 3 weeks

- Top Emitters: Interaction of sunlight with volatile organic compounds (VOCs) – including methane – and nitrogen oxides (NOX) emitted largely by human activities

Hydrofluorocarbons

(HFCs)

- GWP: GWP 20 years: 3830 | GWP 100 years: 1430 | (GWP of most commonly used HFC)

- Atmospheric Life Span: 15 years

- Top Emitters: Human-made. They are primarily produced for use in refrigeration, air-conditioning, insulating foams and aerosol propellants, with minor uses as solvents and for fire protection

Global Warming Potential (GWP) is a metric that compares the ability of different greenhouse gases to trap heat in the atmosphere relative to carbon dioxide (CO2) over a specified time period, typically 20 and 100 years. Therefore, CO₂ is assigned a GWP of 1. The GWP of other gases varies depending on their ability to absorb thermal radiation, their atmospheric lifetime, and the time horizon consided.

Radiative Forcing is the change in the net, downward minus upward, radiative flux (expressed in Watts per square metre) at the tropopause or top of atmosphere due to a change in an external driver of climate change, such as, for example, a change in the concentration of carbon dioxide or the output of the Sun.

Hu, A., Xu, Y., Tebaldi, C. et al. Mitigation of short-lived climate pollutants slows sea-level rise. Nature Clim Change 3, 730–734 (2013).

Source: https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate1869

Why reducing SLCPs matters?

Reducing SLCPs is essential for limiting near-term climate warming due to their high global warming potentials and strong radiative forcing. Unlike CO₂, SLCPs respond quickly to mitigation, offering immediate climate benefits.

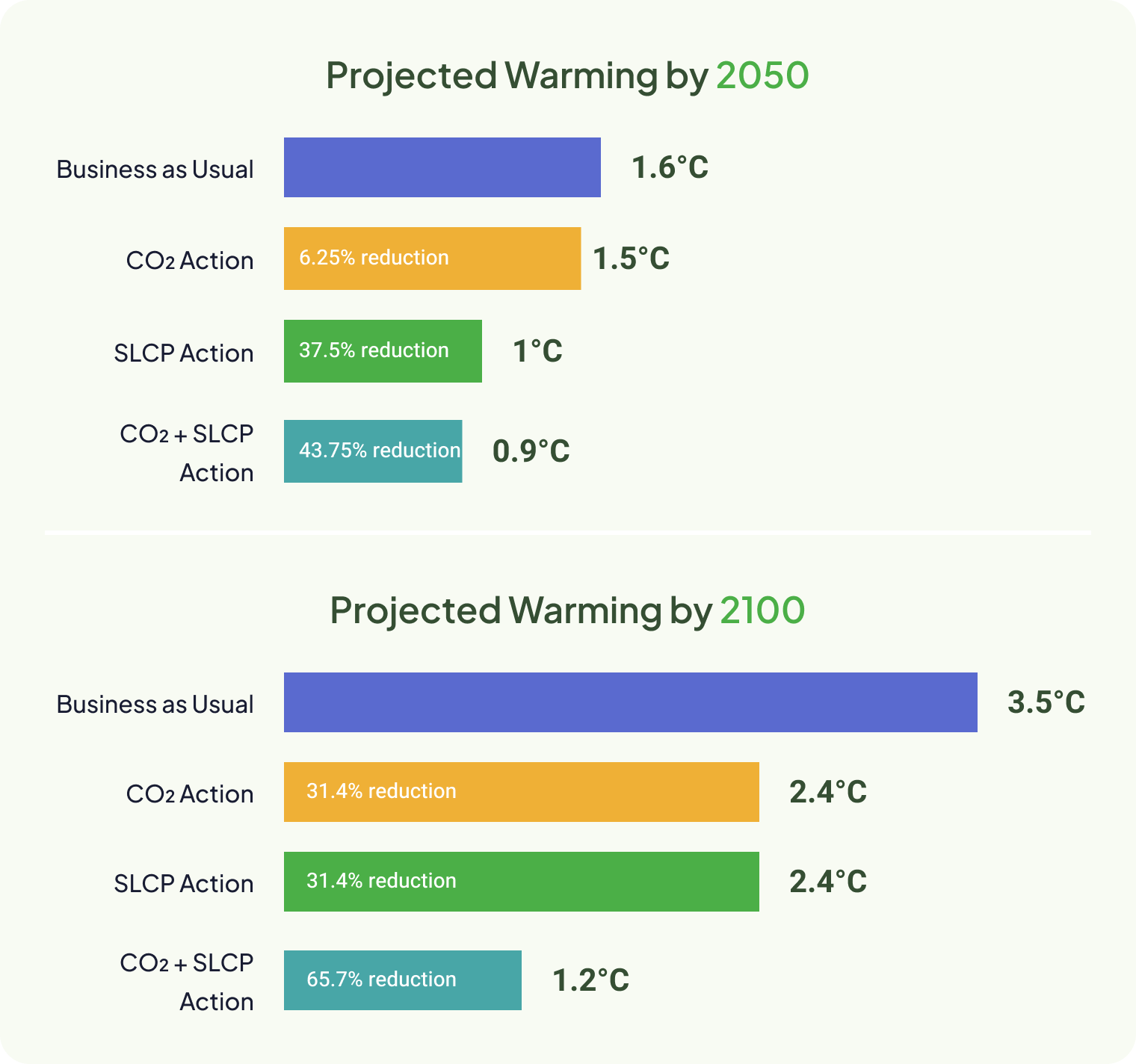

In a business-as-usual (BAU) scenario, global temperatures could rise by 1.6 °C by 2050 and reach 3.5 °C by 2100. Cutting carbon dioxide (CO₂) emissions can reduce this warming by about 0.1 °C by 2050 and by 1.1 °C by 2100. Reducing only short-lived climate pollutants (SLCPs) like methane and black carbon can lower warming by around 0.6 °C by 2050 and 1.1 °C by 2100. This highlights the importance of SLCP mitigation in the short term, while CO₂ reduction is critical in the long term to limit warming to below 2 °C.

The SLCP–SO₂ Paradox

Mitigating Short-Lived Climate Pollutants (SLCPs) such as black carbon and methane provides immediate benefits for climate and air quality. Many sources of these pollutants—like burning fossil fuels (especially coal and oil) and industrial activities—also emit sulfur dioxide (SO₂). SO₂ forms sulfate aerosols that reflect sunlight, creating a short-term cooling effect on the atmosphere.

When cleaner technologies and fuels reduce SLCP emissions, SO₂ emissions often decrease too, which can lead to a temporary, localized rise in surface temperatures due to the loss of aerosol-induced cooling. At the same time, SO₂ contributes to acid rain, harming ecosystems, infrastructure, and human health.

This effect has been observed globally—from U.S. air quality programs to China’s pollution controls and India’s emission drops during lockdowns—highlighting the complex climate–air quality interactions.

In the long run, strategies that cut SLCP emissions—such as switching to cleaner energy, improving combustion efficiency, and reducing reliance on coal—also reduce SO₂ pollution, resulting in lasting improvements for climate, air quality, and public health.